As the house lights dim at the DeVos Performance Hall and the solemn opening chords foreshadow his fate, Don Giovanni is onstage caressing an all-too-willing Donna Anna. And here, before the first word is sung, is the key to the opera: is Giovanni a criminal rapist (whom we must surely condemn) or a suave if amoral seducer (whom we can reluctantly admire)?

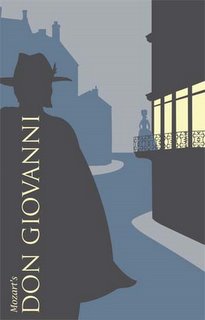

Matthew Lata's staging--like Seattle's, in January--seems to favor seduction. Yet the Don--abetted by Leperello--callously slits the Commendatore's throat when he comes to his daughter's defense. Now we're into the realm of film noir: a leading character of dubious morality, a story updated to Seville in 1936, and a setting full of shadows and shifting shapes.

In the Opera Grand Rapids production, Christopher Schaldenbrand makes Giovanni a convincing, masculine force who lives life (and goes to his doom) according to a personal code of honor. As in Seattle, he is surrounded by compromisers: the jilted Donna Elvira still loves him, Donna Anna never admits that her lust caused her father's death, Don Ottavio waits like a schmuck for her grieving to end (and has two of the night's best arias along the way), Leperello steals his master's food. Only Zerlina, the savvy, sexy peasant girl, seems to have the right notion of situational ethics, as do her counterparts in Mozart operas generally.

Though the production was well sung, inventively staged and impressively lit, Grand Rapids isn't really opera country. The DeVos and Van Andel families--founders of Amway--have underwritten the major athletic and cultural facilities in Grand Rapids; that's not a bad thing: the concert hall is a jewel of a theater. And if, three weekends of the year, the house stages grand opera, that's all to the good.