The American dream would have it that you can do or be anything you want...if you just want it enough and work hard enough. (That's a big lie, of course; it undermines the way Americans behave at home and the way we see the rest of the world.) Books and movies love to tell the Horatio Alger story of newsboys and bootblacks who lifted themselves from poverty to middle-class respectability by dint of hard work. So far, so good, but you don't become a world-class athlete just by practicing long hours; you have to start with talent. You don't make a mint on Wall Street (or Main Street) just because you're greedy and ambitious; you have to be smart enough to know how the system works...and then get lucky. But for every natural athlete who washes out of spring training, for every math whiz who ends up driving a cab, there's still that nagging doubt: I could have been a contender.

Which brings us to France and its wines. Aubert de Villaine's family owned some vines behind the village church in Vosne-Romanée. Mae-Eliane de Lencquesaing's family owned vines in Pauillac; Thierry Manoncourt's family owned vines on the slope leading up to Saint Émilion. Their families all paid hefty sums, in generations past, because those were already highly regarded parcels, and when the time came to "classify" the vineyards of France, they were, quite naturally, placed at or near the very top. But famous vineyards like these (Domaine de la Romané-Conti, Château Pichon-Lalande, Château Figeac, respectively; that's Pichon in the photo, above) represent the tiniest fraction of all the wine made in France. They get a disproporionate amount of atttention, and they bring in substantially more revenue per bottle than average.

Which brings us to France and its wines. Aubert de Villaine's family owned some vines behind the village church in Vosne-Romanée. Mae-Eliane de Lencquesaing's family owned vines in Pauillac; Thierry Manoncourt's family owned vines on the slope leading up to Saint Émilion. Their families all paid hefty sums, in generations past, because those were already highly regarded parcels, and when the time came to "classify" the vineyards of France, they were, quite naturally, placed at or near the very top. But famous vineyards like these (Domaine de la Romané-Conti, Château Pichon-Lalande, Château Figeac, respectively; that's Pichon in the photo, above) represent the tiniest fraction of all the wine made in France. They get a disproporionate amount of atttention, and they bring in substantially more revenue per bottle than average.

But they don't try to be something they're not. You'll never see de Villaine adding syrah to his wines to beef them up, for example, not just because it would be illegal and deceptive, but because land owners, grape growers and wine makers in France (generally, generally) play by the rules. If your property is within the demarcation of St. Émilion, for example, the wine you make is "St. Émilion," and sells for something like $20 a bottle, twice that (and up) if you're in the Grand Cru classification, but if you're next door, it's generic Bordeaux, period, and it doesn't matter how hard you try or how much you want to be in the high-priced club, you'll never get in. For you, $6. Same grape varieties, similar viticultural practices, slightly higher yields, perhaps, but essentially the same wine-making techniques, and still $6.

Hey, that's not fair, you may say, as an egalitarian American visitor who might discern little difference between wines made.from grapes grown only a few hundred meters down the road. At which point the French look at you quizzically, like a dog trying to understand what you're saying. A resigned, gallic shrug of the shoulders, "Eh ben, c'est comme ça." That's just the way it is.

The wine geeks will tell you that Romanée-Conti's grapes are hand-coddled and require additional labor, its expensive barrels newer. No doubt true. But those are costs de Villaine and his fellow aristocrats can incur because he gets a higher price in the first place. To stick with Bordeaux, where nearly half the production of 10,000 estates is sold as "generic" Bordeaux or the slightly better Bordeaux Supérieur, the growers are hemmed in by the distribution system: Bordeaux wines are sold through 400 or so businesses called négociants, who purchase bottles at the lowest possible price.

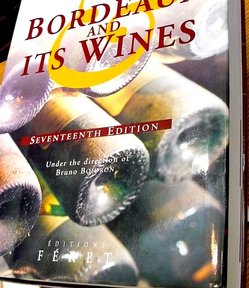

You want a road map? It's called the Féret, a 2,300-page doorstop listing 7,400 estates (detailed entries for the top 1,800 of them), 14,500 wine labels, hundreds of négociants and related suppliers, and a 200-page index with 30,000 entries. It sells for $295 on Amazon.

You want a road map? It's called the Féret, a 2,300-page doorstop listing 7,400 estates (detailed entries for the top 1,800 of them), 14,500 wine labels, hundreds of négociants and related suppliers, and a 200-page index with 30,000 entries. It sells for $295 on Amazon.

All is not grim, however. Slowly, slowly, a few enlightened châteaux are emerging from the tight web of the big Bordeaux négociants. They don't escape entirely, but manage to catch the attention of individual importers. Here in Seattle, Chateau St. Martin is a company that direct-imports estates from St. Emilion. In New York, Daniel Johnnes of Daniel Boulud's restaurant is bringing in a few estates, but they are not many. (Elin McCoy wrote just yesterday about the frustrations faced by the non-celebrities for Bloomberg News.) And there are tons of everyday, non-celebrity wines here; the Bordeaux region produces as much wine as California.

The best position: own a châateau and a négoce business, like Dominique Meneret (who distributes his Château Brondeau through Domaines Meneret-Audy, or Allan Sichel (photo, left) of Château Angludet, Château Palmer and Maison Sichel). Then you can afford to go on the road with your own wines. Second-best position, have a deep, deep pocket, like Per Landin, the Swedish-born owner of Château Parenchère, whose day job is overseeing the Daxin petroleum empire (with an office in Seattle, to supply bunker fuel to Alaska-bound freighers). Landin bought Parenchère only a couple of years ago; it's a marvelous property at the eastern end of the Gironde, with a stunning views from the terrace across its manicured vineyards. And even here, with a resident vineyard manager and a full-time marketing director, it's not an easy job to sell the wine; it's not "famous" enough.

The best position: own a châateau and a négoce business, like Dominique Meneret (who distributes his Château Brondeau through Domaines Meneret-Audy, or Allan Sichel (photo, left) of Château Angludet, Château Palmer and Maison Sichel). Then you can afford to go on the road with your own wines. Second-best position, have a deep, deep pocket, like Per Landin, the Swedish-born owner of Château Parenchère, whose day job is overseeing the Daxin petroleum empire (with an office in Seattle, to supply bunker fuel to Alaska-bound freighers). Landin bought Parenchère only a couple of years ago; it's a marvelous property at the eastern end of the Gironde, with a stunning views from the terrace across its manicured vineyards. And even here, with a resident vineyard manager and a full-time marketing director, it's not an easy job to sell the wine; it's not "famous" enough.

There's a marketing plan in the works for Bordeaux, a ten-year plan not for the two or three dozen famous names but for the other ten thousand. The campaign will target casual drinkers who don't care a drop about terroir; it will capitalize on the elegance suggested by the term "château." There will be music, there will be wine, there will be romance. The tagline: "And the bottle on the table is Bordeaux."

You read it here first. Meantime, if your property's in the right place, you've got a seat at the game; after that, it's all in how you play your cards. Jacques or better to open, but remember that the VIPs (the Pichons and Palmers and Figeacs of the world) are playing at the high rollers' table, out of your league.

The answers to yesterday's quiz: top row, left to right: Brondeau, Parenchere; bottom row, Couronneau. Lamothe. The people: top row, left to right: Christian Piat (Couronneau), Anne Néel (Lamothe); bottom row, Dominique Meneret (Brondeau), Per Landin (Parenchère).

Once again, we acknowledge the folks who made this trip possible. Our delegation of wine writers was invited and hosted by the Syndicat Viticole of Bordeaux & Bordeaux Supérieur, also known as Planète-Bordeaux, the umbrella organization for some 4,000 growers and their annual production of 500 million bottles of wine. (Hope we didn't drink it all!) Many thanks for your thoughtful planning, patient explanations and generous hospitality.

So right about today's casual drinker loving music, wine, and romance Ron. Me too. The 'best seat' though is at a chateau around a huge dining table piled with regional delicacies from country pates to roast duck, and surrounded by the owner's family and friends. The centerpiece is a dozen or more open bottles of both white and red Bordeaux Superieur.