Three new books about food. The first, John F. Mariani's How Italian Food Conquered the World, was reviewed yesterday), Today, two more.

Three new books about food. The first, John F. Mariani's How Italian Food Conquered the World, was reviewed yesterday), Today, two more.

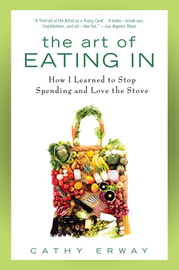

Cathy Erway is the opposite of Mariani, throwing herself into a first-person blog, NotEatingOutInNY.com. While not as sappy and pretentious as Julie Powell's "The Julia Project," its premise is no less annoying: "Look at me, I'm going to do something no one like me, who has a decent job and lives in New York has ever done before: I'm not going to eat out, I'm not going to order in, I'm going to cook all my meals at home for the next two years."

She dutifully types out recipes, doubts and triumphs, concerns about her social life, and, mission accomplished, writes a book about her experience: "The Art of Eating In: How I Learned to Stop Spending and Love the Stove." How do you not eat out if you're on a date? Make dinner together at home, and organize supper clubs.

Early on, Erway quotes Mariani's claim (in "America Eats Out") that American restaurants all seem to have a gimmick (or, more likely, a recognizable theme). But staying home is Erway's own gimmick. She doesn't exactly "dumpster-dive," but comes close, calling her quest "urban foraging." She gets off a couple of good lines along the way: "the world is our oyster bar" and "Little lamb meatball, who made thee?" But overall, "Not Eating Out" suffers from a tedious writing style and a treacly moralism, part Thoreau and part Holden Caulfield. Is this a coming-of-age memoir, an anti-materialist manifesto or a chirpy cookbook? Erway's many admirers claim it's all three (SeriousEats.com even named it one of 2010's top ten cookbooks), but that's asking a lot more than this delivers. Better by far is her new blog, LunchAtSixPoint.com, about urban gardening and "reviving the working class lunch." It's still a bit too chirpy and self-conscious for my taste, but Erway has lost the preachy tone.

What does deliver is Kurt Timmermeister's "Growing a Farmer."

Anyone who's lived in Seattle for the past couple of decades has seen the evolution of Capitol Hill, has watched Broadway transform itself from a battle-scarred no-man's land and freak show to an increasingly gentrified thoroughfare. Anchoring Broadway for much of that time was Café Septième, which its owner, Kurt Timmermeister, had moved up the hill from Belltown (where it was replaced by Marjorie's and then Buckley's). Septième became a Capitol Hill institution, whether for morning coffee and pastries or nighttime drinks and steaks. The usual complaints: one customer's leisurely dinner would be another's nightmare, but Septième also provided work for a squad of servers who would later move into full-time writing, chief among them Dan Savage.

The best parts of Timmermeister's book read like "procedurals," in the same way that the first look at Anthony Bourdain's "Kitchen Confidential" (excerpted as "Annals of Gastronomy, Hell's Kitchen") made such an impact in "The New Yorker" exactly eleven years ago this week. (And how far we've all come since those innocent, pre-Food Channel days!)

Consider, for example, the chapters on killing chickens or slaughtering pigs. Farming isn't just about deracinating vegetables or tugging at udders, it's about slitting throats, too. We may buy pork chops on styrofoam trays wrapped in plastic, but Timmermeister knows better. "I feel that food is intrinsically good. Food is from the earth. It provides us with nutrition to live. It is the source of all life, it has the power to make us healthy."

Standing in opposition, symbolically and practically, are the public health authorities. "Their view," he writes, "is that food is intrinsically dangerous." Rather than fight the federal Food and Drug Administration and the Washington State Department of Agriculture, he stops selling raw milk and raw butter.

How did Timmermeister get from Broadway to a self-sufficient, 12-acre farm, two thirds of it pastureland, on Vashon Island? The journey unfolds over two decades, as the urbanite becomes, first, a suburban homesteader, then a cautious gardener, before selling Septième and acquiring, in its stead, a Jersey cow named Dinah. His days become defined by the bookends of a farm, morning chores and evening chores. The four dozen birds and beasts (chickens, ducks, cows, sheep, pigs, dogs) on his property have to be milked, watered and fed. He has no farmhouse wife to help, no farmhouse kids, only a Mexican laborer (without whom, it's clear, the place would fall apart).

Craigslist is a huge help (for used tractor parts, for baby pig "weaners"). Two-day-old chicks come by US Mail. When it's time for the chickens to be dispatched, the wings get fed to the pigs, "smart, attentive, aggressive, stubborn and charming." Before Timmermeister brings himself to the painful business of killing a pig, he takes the reader through the agony and the joy of buying a gun. The dairy prospers as Kurtwood Farm, as it's now known, begins to produce a highly regarded, creamy cows milk cheese called Dinah.

And once a week, Timmermeister opens his kitchen table to a dozen visitors for a farmhouse dinner, a multicourse feast produced almost entirely from his own land (exceptions made for flour and salt). And yes, there's plenty of farmhouse butter.

How Italian Food Conquered the World, by John F. Mariani, Palgrave Macmillan, 270 pages, $25

The Art of Eating In, by Cathy Erway, Gotham Books/Penguin, 320 pages, $16

Growing a Farmer, by Kurt Timmermeister, W.W. Norton, 336 pages, $24.95

Leave a comment