Some of Puglia's olive groves, extending to the Adriatic, are seen from the village of Ostuni.

PUGLIA, Italy--We're along the heel of the Italian boot, a region that produces almost half of Italy's olives and olive oil. There are somewhere between 50 and 60 million olive trees here in Puglia, twelve or thirteen times as many trees as people (4 million). From Ostuni, an ancient village on the edge of the Murgia plateau, you look toward the Adriatic, five miles to the east, and see nothing but olive trees, many of them centuries old, half a million acres all told. That's about the same area as all of Pierce County.

The region lacks rivers and doesn't get much rain, so its agricultural potential, down on the flatland, is pretty much limited to olives and grapes. (Puglia is also Italy's most prolific grape producer, with powerful reds like Primitivo--Zinfandel's identical twin--that ripen perfectly in the cool Mediterranean breezes of the Salento peninsula.) But it is the olives, specifically, that concern us here.

In 2007, the New Yorker published a 5,500-word article titled "Slippery Business" about colossal levels of fraud in the sale of what's known as Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Two thirds of what's sold in American supermarkets as EVOO, estimates Tom Mueller, the article's author, isn't the real thing at all. Oil from olives, perhaps, but hardly the rigorously controlled and strictly defined "first press." It's even worse in the food service industry, with adulterated soybean and sunflower oils regularly passed off as higher quality olive oil. What's more, any manner of imported vegetable pressings from Greece or Turkey or Tunisia are regularly offloaded in ports along Puglia's coast, processed to remove unwanted characteristics, and resold as "Italian." (That step is actually legal as long as the intent isn't to mislead consumers). But then, often with the assistance of a corrupt bureaucrat or two, the stuff is relabelled as olive oil and often "transformed" into extra virgin.

In 2007, the New Yorker published a 5,500-word article titled "Slippery Business" about colossal levels of fraud in the sale of what's known as Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Two thirds of what's sold in American supermarkets as EVOO, estimates Tom Mueller, the article's author, isn't the real thing at all. Oil from olives, perhaps, but hardly the rigorously controlled and strictly defined "first press." It's even worse in the food service industry, with adulterated soybean and sunflower oils regularly passed off as higher quality olive oil. What's more, any manner of imported vegetable pressings from Greece or Turkey or Tunisia are regularly offloaded in ports along Puglia's coast, processed to remove unwanted characteristics, and resold as "Italian." (That step is actually legal as long as the intent isn't to mislead consumers). But then, often with the assistance of a corrupt bureaucrat or two, the stuff is relabelled as olive oil and often "transformed" into extra virgin.

The fraud is relatively easy to detect analytically but almost impossible to prosecute. Not even a notorious case, in Spain 20 years ago, in which 300 people died from adulterated olive oil, slowed the tide of fraud. In Italy, on the regional and national level, the crooked operators are very well connected politically. Supposedly independent industry associations are toothless. The European Union doles out massive subsidies to the "olive oil" producers but has yet to recoup any of its fraudulently obtained grants. When Italy's respected Guarda di Finanza (the military police arm of the Finance Ministry, responsible for drug smuggling, border patrol, and the like) does manage to act, the bad guys stall until the statute of limitations runs out. Experts who challenge the Big Oil producers are regularly sued for slander. Stateside, the various agencies responsible for food safety and domestic security have, thus far, claimed that mislabeled olive oil isn't a big priority.

The fraud is relatively easy to detect analytically but almost impossible to prosecute. Not even a notorious case, in Spain 20 years ago, in which 300 people died from adulterated olive oil, slowed the tide of fraud. In Italy, on the regional and national level, the crooked operators are very well connected politically. Supposedly independent industry associations are toothless. The European Union doles out massive subsidies to the "olive oil" producers but has yet to recoup any of its fraudulently obtained grants. When Italy's respected Guarda di Finanza (the military police arm of the Finance Ministry, responsible for drug smuggling, border patrol, and the like) does manage to act, the bad guys stall until the statute of limitations runs out. Experts who challenge the Big Oil producers are regularly sued for slander. Stateside, the various agencies responsible for food safety and domestic security have, thus far, claimed that mislabeled olive oil isn't a big priority.

Who's to blame? In Italy, at any rate, the buck stops at the very top. "[Former Prime Minister Silvio] Berlusconi's role is indirect but meaningful in olive oil crime - creating and enhancing a sense that law and order is irrelevant," Mueller wrote to me in an email.

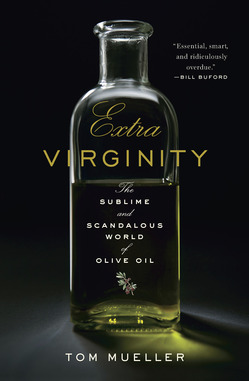

Mueller, who lives in Italy and has family roots in eastern Washington, has now expanded his New Yorker article into a book titled "Extra Virginity." He updates the various court cases he described (no one went to jail) and widens the horizon of the Italian frauds to the rest of the world.

We'll have that part of the story tomorrow.

Leave a comment