For the dozen guests seated at the counter of the restaurant at Second and Battery in Belltown, the sushi master is in the house. They know that Shiro Kashiba, who opened Seattle's first sushi bar, the Maneki, in 1966 and semi-retired four years ago, nonetheless comes to work twice a week, Tuesdays and Thursdays. Occupying the inside, spot-lit position behind the sushi counter, Shiro (no one calls him anything else) is far more outgoing than most sushi chefs but it is a professional friendliness. He smiles readily but pays close attention to the guests in front of him. He is a strict but sympathetic teacher, not a show-off chef.

When he first arrived in Seattle, sushi was almost unknown outside the Japanese community. Shiro would hike the Puget Sound beaches and dig his own geoduck; he would take unwanted octopus and salmon roe from fishermen along the Seattle waterfront. He would go clamming on the shores of Puget Sound and dig his own geoduck because there was no commercial catch. Eventually, it would start selling for 89 cents a pound in local markets; now, 30 years later (with increased demand and the rise of a sushi-mad Chinese middle class), geoduck is $20 a pound.

By training and temperament, Shiro is a traditionalist, and his restaurant, Shiro's, is the archetype of a traditional sushi parlor. Guests who expect (and demand!) unusual peparations like "fusion rolls" are politely shown the door with the suggestion that Wasabi Bistro, a block south, might be more accommodating. Myself, I remember telling Shiro, after half a dozen visits, that I was ready for something "more adventurous." (I might as well have asked Bach to improvise "An American in Paris.") At any rate, Shiro set me straight: the adventure is created within a formal framework, in the pleasure of each piece of fish, in the satisfaction of the experience.

By training and temperament, Shiro is a traditionalist, and his restaurant, Shiro's, is the archetype of a traditional sushi parlor. Guests who expect (and demand!) unusual peparations like "fusion rolls" are politely shown the door with the suggestion that Wasabi Bistro, a block south, might be more accommodating. Myself, I remember telling Shiro, after half a dozen visits, that I was ready for something "more adventurous." (I might as well have asked Bach to improvise "An American in Paris.") At any rate, Shiro set me straight: the adventure is created within a formal framework, in the pleasure of each piece of fish, in the satisfaction of the experience.

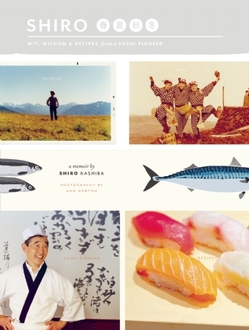

His memoir, "Shiro," is an unaffected gem. The first two-thirds recount his journey from Kyoto to Seattle, passing via years of slog in Tokyo's Ginza district. Ambitious, he persuaded a Seattle restaurateur named Ted Tanaka to hire him, and, in 1966 he arrived in Seattle. Within four years, he had opened the citys first full-service sushi bar, The Maneki. Four years later, he married Ritsuko, a fellow foreign student at Seattle Community College. In 1972 he opened Nikko (which he would sell to Westin Hotels); in 1986, Hana; in 1994, Shiro's.

The book itself is a physical delight. First off, it smells good, a refreshing cedar aroma. (The book's designer, Joshua Powell, explains that the paper used for the memoir section is known as "Yu Long Cream woodfree" and the for the recipe section "Chinese Woodfree," both uncoated.) The content is full of memorabilia: snapshots, old menus, airletters from his patron, maps, caligraphy, sketches, watercolor illustrations. The first two-thirds are Shiro's memoirs, told with good-humored modesty. It's a tribute to Shiro's character that there's not a trace of braggadocio; perhaps because it's about an unfamiliar culture that none of this gets boring. (Credit, too, to Shiro's Seattle-based translators, Bruce Rutledge and Yuko Enomoto.) Shiro himself comes across as an ideal, if somewhat formal host, whether he's preparing your dinner at the sushi counter in Belltown or Bill Gates's annual c.e.o. dinner in Medina.

And then, just when you're pleasantly sated, along come another 100 pages of recipes and tips: how to cook short-grain rice, how to prepare it for sushi, how to make nigiri sushi (with lovely photographs by Ann Norton), how to clean smelt, how to cut fish for sashimi, how to season and eat sushi (no dunking in soy sauce!). Plus a handy list of terms to use at the sushi counter. (Oaiso: Check, please!)

"I hope that long after I'm gone, traditional sushi will find a way to adapt to different regios of the world," Shiro concludes. "With smart stewardship and respect for the oceans, the Pacific Northwest can remain a paradise for sushi lovers."

But there are storm clouds on the sushi horizon. More of the Chinese middle class have discovered the allure of sushi, driving up the price of fish; more middle-class Americans find it sushi too expensive; fewer of Japan's trained sushi chefs want to work in the US; there's less good fish to go around.

In the meantime, Shiro Kashiba's memoir should be read and taken to heart by every food lover for its celebration of simplicity and its reverence for nature's bounty.

"I didn't want this to be just another recipe book," John Howie says. He opens his cookbook with a ten-page memoir (no illustrations) that recounts his boyhood and adolescence, culminating with a stint, at the age of 16, running the line at a fine-dining restaurant. At one point in his career, he's the chef at a spot frequented, post-game, by the Sonics, an association that provides good connections down the road. He joins Restaurants Unlimited (Cutters, Palomino, etc.), becoming the chef and GM at Triples, then opens Palisade. After 14 years with RUI, he sets off on his own, opening Seastar, in 2002, with the vision of making it the premier seafood restaurant in the Pacific Northwest. Trained by RUI to pay attention to the smallest detail, Howie nonetheless makes a wholehearted commitment to his employees. He now runs four stores (Seastars in Bellevue and Seattle, a steakhouse in Bellevue and a sports bar in Seattle) with his key personnel as vested business partners. The sports theme continues to this day: Howie represents Seattle every year at the annual Taste of the NFL dinner on the eve of the Superbowl. There's a whiff of piety at the end of the book, when he describes how his staff gathers before service begins, joins hands and thanks God, but it's quite genuine.

"I didn't want this to be just another recipe book," John Howie says. He opens his cookbook with a ten-page memoir (no illustrations) that recounts his boyhood and adolescence, culminating with a stint, at the age of 16, running the line at a fine-dining restaurant. At one point in his career, he's the chef at a spot frequented, post-game, by the Sonics, an association that provides good connections down the road. He joins Restaurants Unlimited (Cutters, Palomino, etc.), becoming the chef and GM at Triples, then opens Palisade. After 14 years with RUI, he sets off on his own, opening Seastar, in 2002, with the vision of making it the premier seafood restaurant in the Pacific Northwest. Trained by RUI to pay attention to the smallest detail, Howie nonetheless makes a wholehearted commitment to his employees. He now runs four stores (Seastars in Bellevue and Seattle, a steakhouse in Bellevue and a sports bar in Seattle) with his key personnel as vested business partners. The sports theme continues to this day: Howie represents Seattle every year at the annual Taste of the NFL dinner on the eve of the Superbowl. There's a whiff of piety at the end of the book, when he describes how his staff gathers before service begins, joins hands and thanks God, but it's quite genuine.

The book is filled with candid photographs of the staff, and not a few tributes penned by friends and family along the lines of "John cares about people" and "We will not compromise on quality." David Putaportiwon, one of the partners at Seastar, introduced Howie to sushi and is responsible for the illustrated, step-by-step guide to preparing a spicy tuna roll.

The book is filled with candid photographs of the staff, and not a few tributes penned by friends and family along the lines of "John cares about people" and "We will not compromise on quality." David Putaportiwon, one of the partners at Seastar, introduced Howie to sushi and is responsible for the illustrated, step-by-step guide to preparing a spicy tuna roll.

Erik Liedholm, the company's wine director from the outset, won "Best New Wine List in America" honors from Food & Wine magazine. Recuited by Howie from the Washington Wine Commission, Liedholm brings a refreshing informality to the stuffy world of wine. Yes, there are high-roller, "life's too short" picks for each recipe, but alternate "just because it's inexpensive doesn't mean you're cheap" picks. A good example: for a main course of plank-roasted portobello mushrooms, the expensive pick is the stunning Beaux Frères pinot noir from Oregon's Red Hills of Dundee retailing for $50 (and up), but the moderately priced alternate is no less stellar: Stoller, a new producer from the same region whose wine sells for $25.

It may not be possible for a home chef to cut Copper River salmon carpaccio on a meat slicer, but even some of the more exotic recipes (Hot & Sour Thai Shimp Soup, for example) only require that you follow instructions closely and use the specifically recommended ingredients. Don't go off winging it!

At the book's launch party at Seastar last week, in anticipation of a decade of operation, Howie reflected on the title of his book, "Passion & Palate." "Passion, first, because you have to have it in this business," he told me. "But Palate is no less important, because if you don't have it, your food won't taste good." The subtitle, "Recipes for a Generous Table," is no less revelatory. Howie has always been among the most generous chefs in town, never saying no to a charitable donation. "For me, it's just the right thing to do," he says.

Shiro: Wit, Wisdom and Recipes from a Sushi Pioneer, by Shiro Kashiba with photographs by Ann Norton, Chin Music Press, 320 pages, $20

Passion & Palate: Recipes for a Generous Table, by John Howie with photographs by Angie Norwood Browne, ShinShinChez, 224 pages, $42

Leave a comment