In 1965, a gifted, 42-year-old Korean tenor named Johsel Namkung, who had emigrated to Seattle 18 years earlier, gave a farewell recital, singing Schubert's Schwanengesang (literally "Swan Song"), and turned his artistic career from music to photography. It was a surprising change of course; except for the occasional famous name like Ansel Adams, photographers were not taken seriously by the art world. Yet, with the Sierra Club leading the way in 1961 with a popular volume of nature photographs by Eliot Porter titled In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, a new genre of lavish, coffee-table publications was on its way.

Namkung felt that photography competed as an art form with oils and watercolors, so it needed to be presented in large formats. For the next several decades, like a European plein-air painter, he would hike into the wilderness bearing the tools of his trade: a tripod, a heavy view camera, and the luxury of patience. In his book, "Ode to the Earth" (pbulished by Cosgrove Editions in 2006), Namkung described "the loneliness and exultation" of reaching the top of the mountain, "standing all by yourself with your camera."

Namkung was born in rural Korea in 1919. His father, a theologian with a graduate degree from Princeton, translated the Bible into Korean. But young Johsel's interest was music, specifically the genre of songs known as Lieder: German poems celebrating the beauty and discipline of nature. At the age of 16, he performed his own translation of a Lied by Heine and won a national competition. The prize allowed him to study in Japan, where he won another national competition. He also fell in love with a local lass, Mineko.

Both sets of parents opposed the match, so they eloped to Shanghai. Having survived World War II, Johsel and Mineko eventually made their way to Seattle Pacific University, where they were welcomed by missionaries who had befriended the Namkung family in Korea. Johsel quickly moved to the University of Washington's School of Music, and a burgeoning interest in photography brought him in contact with Seattle artists George Tsutakawa, Paul Horiuchi, Mark Tobey, and Kenneth Callahan. Because he spoke several Asian languages fluently, Namkung also worked for Northwest Orient Airlines.

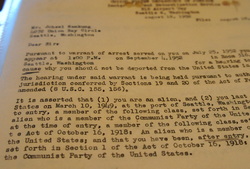

Then, in the early 1950s, on a routine trip to visit relatives in Korea, Namkung carried a letter (at the request of a friend on the UW faculty) that he delivered to a North Korean bureaucrat. Unfortunately, this was during the tense McCarthy era, and sentiment against the Communist North ran high. On his return to the US, Namkung was questioned by the House Un-American Activities Committee and branded a communist sympathizer; the Immigration & Naturalization Service ordered him deported.

Then, in the early 1950s, on a routine trip to visit relatives in Korea, Namkung carried a letter (at the request of a friend on the UW faculty) that he delivered to a North Korean bureaucrat. Unfortunately, this was during the tense McCarthy era, and sentiment against the Communist North ran high. On his return to the US, Namkung was questioned by the House Un-American Activities Committee and branded a communist sympathizer; the Immigration & Naturalization Service ordered him deported.

That touched off a ferocious legal challenge to the INS. Namkung was fortunate that a courageous, old-fashioned and decent civil liberties lawyer, Ken MacDonald, took up his cause. MacDonald could muster public outrage on behalf of his client, but, more importantly, he knew how to work the political byroads between Seattle and Washington, DC. (To help pay her husband's legal fees, Mineko took a job as as one of the kimono-clad waitresses at Canlis.) In the end, Johsel and Mineko were allowed to remain in Seattle, but it took seven years, and a "private bill" sponsored by the state's congressional delegation to clear his name.

In the midst of all the political uncertainty, Namkung embarked on a new career as a photographer. His day job was shooting for the UW School of Medicine, which left plenty of free time for his exploration of nature. From Seattle's Frink Park to the Telanika River in Alaska, from Shi Shi beach on the Washington coast to Weston Cove in California, Namkung would hike into remote locations carrying a tripod and a 35-pound 4x5 Sinar view camera.

Most of the time he would photograph details, not great vistas. "Questions, not answers," is how he describes it. Longer exposures, abstract forms, animal shapes, bulbs of purple kelp. Undulations of green and russet at Steptoe Butte; orange sky reflected in Lake Wenatchee. The image of the Yakima River as it begins to freeze over, for example, required hours of waiting until the moment was just right.

The artist, Namking believes, observes the essence of things and finds beauty in the most mundane. Creative execution is like performing music on stage.

It's gratifying that Johsel Namkung's story has three unrelated yet happy endings.

It's gratifying that Johsel Namkung's story has three unrelated yet happy endings.

First, his friend and colleague of 40 years, Dick Busher, has brought out a remarkable new book of 100 photographs, a third of them never published before, titled "Johsel Namkung: A Retrospective." The book is bound with Chinese silk fabric, and printed with ultra high resolution technology, as befits Namkung's extremely detailed images. The book is available in a standard hardcover edition ($175) as well as two deluxe formats. Details from Cosgrove Editions, 888-507-7375.

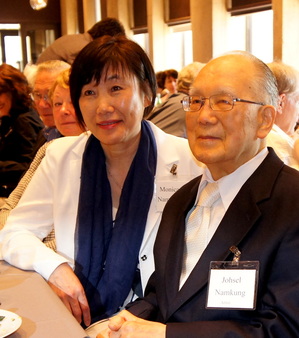

Second, a new romance. After Mineko died of cancer in 1999, after 57 years of marriage, Johsel happened to be sitting next to Monica Jung, a widow who shared his love of music, at a Seattle concert given by Fredrica von Stade. They were married a year later.

And third, yellowing carbon copies of Ken MacDonald's legal correspondence on behalf of Namkung were recently unearthed by MacDonald's son, Doug (former Washington Secretary of Transportation). Ken, now in his mid-90s, presented them to Johsel last month. The binder, titled Six Decades Later, is inscribed: "The miracle is that it all turned out so well, and led to so much wonder and beauty brought into the world."

Leave a comment