Eggplant at one of the three public markets in Palermo, Sicily, February 2009.

A weekend of posts about Sicily. Tomorrow, the joy of Baroque. Today, however, a look into a recent book about cooking in Sicily that misses the mark. (Especially disappointing since it served as one of the inspirations for Maria Hines's excellent new Sicilian restaurant, Agrodolce.)

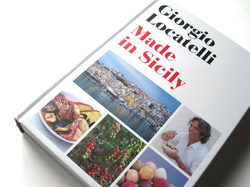

The title is Made in Sicily, and its author, Giorgio Locatelli, is the well-known owner of a popular Italian restaurant, Locanda Locatelli, in London. Locatelli grew up in a restaurant family on one of the Alpine lakes in northern Italy; he didn't travel to Sicily until he'd been a professional chef in Britain for two decades. He reports that he was "completely blown away" by his visit to this "mythological island." As an amateur food historian, he learns that Sicily's cuisine has been influenced by all its Mediterranean neighbors: Greece, Spain, the Arabs. The rich land and teeming sea provide a wealth of riches; "what grows together goes together."

But this (clumsy) sentence is just plain wrong; "...in most of Italy we have an unwritten rule that you never put fish and cheese together, something that the Sicilians happily do all the time and that works." In fact, the Sicilians are the most vocal defenders of the seafood-dairy barrier. (For those who compulsively drown crab fettuccine in cream, top scallops and prawns with parmesan, and dip lobster claws in melted butter, the culinary concept is to preserve the delicate flavor and aroma of fish; a spritz of lemon is all that perfectly fresh seafood needs. Seriously)

There's an enthusiastic endorsement of pasta alla Norma and the unique cheese, ricotta salata, that accompanies it. But a serious misunderstanding of how you prepare pasta con le sarde (and why Sicilians prepare it the way they do): If you don't have any wild mountain fennel, Locatelli says, you can use fennel seeds. Mario Batali would disagree; he coarsely chops some fennel bulb and tosses it with olive oil. Neither is correct. If you don't have wild mountain fennel, you'd be tempted to substitute the bushy green tops of a regular fennel bulb, but it's not quite the same. Some of my Sicilian friends won't make pasta con le sarde unless they have bucatini (hollow spaghetti) and Mediterranean sardines. Of course you can use almost any pasta, but, again, it's something else. You shouldn't call it a Lamborghini if it's a Vespa.

There's an enthusiastic endorsement of pasta alla Norma and the unique cheese, ricotta salata, that accompanies it. But a serious misunderstanding of how you prepare pasta con le sarde (and why Sicilians prepare it the way they do): If you don't have any wild mountain fennel, Locatelli says, you can use fennel seeds. Mario Batali would disagree; he coarsely chops some fennel bulb and tosses it with olive oil. Neither is correct. If you don't have wild mountain fennel, you'd be tempted to substitute the bushy green tops of a regular fennel bulb, but it's not quite the same. Some of my Sicilian friends won't make pasta con le sarde unless they have bucatini (hollow spaghetti) and Mediterranean sardines. Of course you can use almost any pasta, but, again, it's something else. You shouldn't call it a Lamborghini if it's a Vespa.

There is an understanding, in Sicily, that you feed people with whatever you have; and, since most of Sicily is a vast garden, what you have most abundantly is vegetables. Because it is an island, there is a greater emphasis, at least along the coast, on fish, rather than meat.

Locatelli gives four recipes for Sicily's iconic appetizer, caponata (summer, wintrer, Christmas and artichoke-based), reminding us yet again that eggplant was introduced to Sicily "by the Arabs." The dish is not unlike the French ratatouille, assembled from sauteed or deep-fried vegetables, though caponata is often made sweeter by the addition of sugar, raisins, or balsamic vinegar.

The photographs, credited to Lisa Linder, are dark and grainy. There's none of Sicily's sun, none of its optimism. Would it have killed the photographer or the photo editing software to brighten the landscapes by an f/ stop or two? The food closeups, too, could use better styling, better lighting, better color. Linder is a respected photographer for British travel magazines and advertising agencies, but this doesn't appear to be a particularly inspired effort.

It's not until the very end that the reader realizes a serious omission: the section on wine grapes, "compiled" by Locanda's wine director, runs only two pages, with quick descriptions of 11 white and 7 red grape varieties. You'd never know that Sicilian wine is both a symbol of the island's rejuvenation and its escape from the yoke of the Mafia. (Robert Camuto's book, Palmento, recounts this in detail.)

"Very little in this book is complicated, because in Sicily the ingredients are so special they speak for themselves," Locatelli writes. "If you have been to Sicily you will understand. If you haven't been to Sicily, then you must go." No argument there. And we'll get close in my next post.

Made in Sicily, by Giorgio Locatelli with Sheila Keating, Harper Collins, 423 pages, $45

Leave a comment