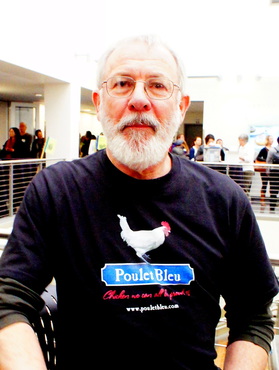

Riley Starks, below, is on a mission to restore the reputation of the noble chicken.

Back in the day, turn-of-the-century, a commercial fisherman named Riley Starks took over a rustic lodge on Lummi, a little island tucked under the Canadian border off the coast of Bellingham at the northeastern tip of the San Juan archipelago. That was the original Willows Inn. Then, shortly after he had hired a dazzling 24-year-old line cook named Blaine Wetzel to run the kitchen, and just as the resort was on the cusp of becoming world-famous, Starks sold the property to a group of local investors.

Back in the day, turn-of-the-century, a commercial fisherman named Riley Starks took over a rustic lodge on Lummi, a little island tucked under the Canadian border off the coast of Bellingham at the northeastern tip of the San Juan archipelago. That was the original Willows Inn. Then, shortly after he had hired a dazzling 24-year-old line cook named Blaine Wetzel to run the kitchen, and just as the resort was on the cusp of becoming world-famous, Starks sold the property to a group of local investors.

(The new owners would quickly remodel the accommodations, reconfigure the dining rooms, and rebrand Willows Inn as a luxury resort with a world-class chef.)

Not one to dwell on opportunities lost or roads not taken, Starks retreated to his own place, Nettles Farm, a 15-minute stroll from the beach on land he'd cleared himself, and set about turning it into a European-style agriturismo, a working farmhouse bed & breakfast. Fussy, thread-count-obsessed tourists should stay away, they won't find turn-down service with imported chocolates on the pillows. Starks sells the farm's produce at a farmstand near the ferry terminal, and offers his guests the novelty (for city-slickers) of real farm experiences like classes in chicken slaughtering ($50 per person plus the cost of the bird, which you then eat for dinner).

Starks, you see, is on a mission: he intends to restore the reputation of the noble chicken. Not, he's quick to say, those plastic "broilers" from an industrial facility that go from hatchling to supermarket styrofoam in under six weeks. Nope, these are more like the most famous of all French chickens, the proud poulet de Bresse.

The Bresse is rich farmland on the left bank of the Saône river that lies between Burgundy and Lyon, and it's here that the local birds reach the height of chickendom. Part of it, sure, is what they eat. But it's mostly their genetic makeup. And herein lies the story of Starks's quest.

Before going further, here's an extract from the official Poulet de Bresse statute:

Bresse Poultry has a "melting" flesh, that this flesh is impregnated with fat right into its smallest fibres and that this fat contains the essential part of the savouriness. To be sure that the Bresse Poultry conserves its qualities to a maximum degree, it must be "cooked inside itself". In this way, the greater part of the intra-muscular fat and even the water it contains will remain inside and the chemical reactions caused by heat, which give the delicate taste, will impregnate the whole bird.

For "biosecurity" reasons, actual Poulet de Bresse birds aren't allowed out of France, but a poultryman named Peter Thiessen, across the BC border in Abbotsford, had been breeding chickens developed from French stock since the 1980s. Better yet, the resulting animals, known as Poulet Bleu for their blue feet, were worth $10 a pound, 20 times the value of a supermarket bird.

Before he passed away last year, Thiessen agreed to sell his flock to Starks, who expects to take possession, in a complex cross-border transaction, by mid-March. By all accounts, the Poulet Bleu is one superb-tasting bird. Just ask culinary director Roy Breiman of Copperleaf Restaurant, who baked 300 mouthwatering chicken-pot-pies for this week's Farmer-Chef Connection event using Poulet Bleu stock; for that matter, ask any of the attendees: luscious!

Says Starks, "This is a chicken we are proud to grow, restaurants can be proud to serve, and you can be proud to eat."

Nettles Farm Bed & Breakfast, 4300 Matia View Dr., Lummi Island, 360-758-7616

Leave a comment