The story has all the elements of a Dan Brown thriller: a forgotten mural by a not-yet-famous artist, but clearly a priceless masterpiece, rescued from oblivion by a cascade of coincidences. It would be almost as dramatic as finding Da Vinci's Last Supper rolled up and forgotten in the plastered wall of a palazzo in Milan.

UPDATE: Several more layers to this story in the 48 hours since this was posted. Much of the new information is in a story I wrote for Crosscut, here. And the Skagit Herald has additional details via the Anacortes Museum.

The Breckenridge family, farmers in Skagit County, somehow acquired the work, which is dated 1941 and signed by William Cumming, the much-loved painter who died four years ago. Tom Breckenridge's father, who taught school in Edison in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, had kept the mural, folded and unseen, in a box with paraphernalia from the county's Junior Livestock Show. His granddaughters used to play hopscotch and practice their long jumps on it.

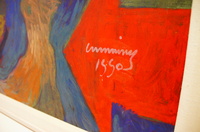

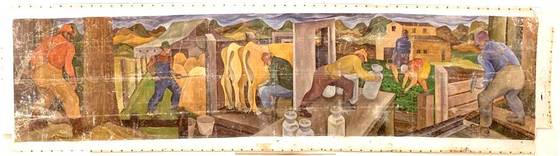

Unfolded, it was 28 feet long and 7 feet wide, divided into six panels, painted in egg tempera that had lost none of its vibrancy over three quarters of a century, panels depicting agricultural activity in the Skagit: felling timber, baling hay, milking cows, loading the milk wagon, picking berries, building fences. It's not actually canvas but sailcloth, three horizontal bands sewn together, the whole thing surrounded by the original grommets. The girls had scuffed up one corner when they used the cloth as a mat to practice their long jumps, right where the artist had signed the piece. But a longtime friend of the artist, John Braseth, who owns the Woodside-Braseth Gallery in South Lake Union, was able to authentic the signature as Cumming's.

Cumming, born in Montana, had come to Tukwila as a youngster. He won art competitions, but disdained formal training; still, he caught the eye of Dr. Richard Fuller, director of the Seattle Art Museum. He was also a hotshot writer and critic; his particular favorites were a group of painters who came known as the Northwest School (or, by others as the Seattle Mystics): Kenneth Callahan, Mark Tobey, Guy Anderson. Cumming seemed to have an intuitive sense of who they were and what they were doing; they had immense respect for his writing, and he, in turn, was awestruck upon finally meeting them in person, in 1937, when he was all of 19 years old. Callahan's wife, Margaret, took young Cumming under her wing.

Within a couple of years, the Works Progress Administration had begun an ambitious program of commissioning work by American artists, writers, historians and photographers around the country. In the Northwest, the Seattle Mystics all got commissions that allowed them to ride out the worst years of the Depression. Cumming, too, got work from the WPA, but as a photographer, not as a painter. "So whatever he did in Mt. Vernon, it wasn't technically a WPA commission," says Braseth. "We still don't know exactly how this came about."

What we do know is that Tony Breckenridge didn't throw away the "tarp." It survived several barn fires; it survived cleaning horse stables and cattle barns. Breckenridge was going to use it to cover a stack of lumber, but when he saw that the "reverse" side was a painting, he folded it up and put it back in the basement. Earlier this year, he told me, he had finally decided to throw it out, but he looked at the picture one more time and was reminded of the Junior Livestock Show. Rather than drag the damn thing to the burn pile, he called Brian Adams at the county parks department; Adams was the man in charge of the County Fair, and might want to use it in an exhibit. Adams came by a week ago and loaded the "tarp" into his truck.

What we do know is that Tony Breckenridge didn't throw away the "tarp." It survived several barn fires; it survived cleaning horse stables and cattle barns. Breckenridge was going to use it to cover a stack of lumber, but when he saw that the "reverse" side was a painting, he folded it up and put it back in the basement. Earlier this year, he told me, he had finally decided to throw it out, but he looked at the picture one more time and was reminded of the Junior Livestock Show. Rather than drag the damn thing to the burn pile, he called Brian Adams at the county parks department; Adams was the man in charge of the County Fair, and might want to use it in an exhibit. Adams came by a week ago and loaded the "tarp" into his truck.

The next day a picture of the mural was in the Skagit Valley Herald, and within hours the story began to ricochet around the Internet. An art collector who lives in the valley alerted Braseth, who asked for a higher-resolution picture of the signature. This weekend, he made the trip to Mt. Vernon and confirmed the mural's authenticity. "I know Cumming's handwriting better than I know my own," he told me. "The way he would do his 'g,' gives it away."

Now the question is, "Who owns it?" Before that, though, comes the more immediate question: who's going to pay to restore it? Already several anonymous benefactors in Skagit County have told Braseth they'd contribute to a restoration fund; there's damage to the corner from the Breckenridge girls using it as a gym mat, there's damage where the linen has been folded and refolded over the decades. Fortunately, no water damage, no major abrasion. Braseth estimates that proper restoration will cost over $25,000.

When the story broke, this past weekend, Braseth estimated the value of the piece at $100,000. Since then, having actually seen the the mural, he's raised his estimate to half a million. But whose property is it?

Cumming never spoke of this particular piece, and to date no written records on its origins have been found. There was a retrospective of his work at the Frye in 2006 which doesn't mention at any commission like this, and none of the agricultural themes show up in his later work. But the style is unmistakeably Cumming's, with expertly rendered human figures captured in his unique stop-motion technique, turning their faces away from the viewer's gaze, blending into their pastel-colored landscapes.

The irony: Cummings was fervent communist who disdained the notion of private property. He saw himself as a teacher first and a painter second. He didn't believe in any distinction between "commercial art" and "fine art." A resolute populist, he wrote in his memoir, Sketchbook, "I hate fine art with all its fuss and crap. Fine art students are brought up in a spirit of contempt for people. Of course I paint for the market. So did Rembrandt. So did Titian." For that matter, so did Diego Rivera, the Mexican muralist ("Man at the Crossroads" in Rockefeller Center), a generation older than Cumming but also a populist, also a communist.

Leave a comment