The letter, in a 6 by 9 yellow envelope, looked like the mailer for a birthday card and bore only a hieroglyphic return address, but the postmark clearly said AMSTERDAM. I opened it to find two typewritten pages on the letterhead of an organization called Stichting A&H Wolff.

The letter, in a 6 by 9 yellow envelope, looked like the mailer for a birthday card and bore only a hieroglyphic return address, but the postmark clearly said AMSTERDAM. I opened it to find two typewritten pages on the letterhead of an organization called Stichting A&H Wolff.

In perfect English, the writer, An Huitzing, introduced herself as the secretary of a foundation devoted to the memory of two German photographers, Annemie and Helmuth Wolff.

Ten years ago [she wrote], a Dutch historian named Simon Kool discovered a cache of photographs made by the Wolffs and embarked on a project to create an exhibit and book about their work.

The Wolffs had started out in Munich, but then, like many Jewish professionals, they moved to Holland in the 1930s. (One of their early clients was a food-processing company, Opekta, owned by Otto Frank, Anne Frank's father.) Among the artifacts that were recovered from the Wolffs' studio after the war was a collection of some 50,000 photographs, including 100 rolls of film taken in 1943, three years after the Nazi occupation of Holland.

The Wolffs had started out in Munich, but then, like many Jewish professionals, they moved to Holland in the 1930s. (One of their early clients was a food-processing company, Opekta, owned by Otto Frank, Anne Frank's father.) Among the artifacts that were recovered from the Wolffs' studio after the war was a collection of some 50,000 photographs, including 100 rolls of film taken in 1943, three years after the Nazi occupation of Holland.

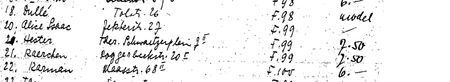

"These contain portraits of 429 private persons, inhabitants of Amsterdam South," Mewr. Huitzing wrote in the letter. "Jews with stars of David, Jews without these stars, non-Jewish inhabitants of South Amsterdam, etc. Names and addresses are written in a receipt book for Mrs. Wolff's financial administration."

Kool, along with friends, founded the Wolff Foundation in 2011. One part of their mission is to track down the people in the photographs. The youngest (who would have been an infant at the time) is 71 today, the oldest is 103. Thus far, the Foundation has located 200 of the 429 subjects. Alice Isaac, pictured here, is number 201.

But why would people pause, in the middle of a war, to have their pictures taken? One obvious answer is for identification papers (or false papers, more likely). Another is for keepsakes to be shared with friends and loved ones in uncertain times. Ironically, a Dutch resistance group earlier in 1943 had firebombed the Public Records Office in order to destroy data used by the Nazis to track down Jews. The Nazis had just opened a Vernichtungslager (death camp) at Auschwitz, 750 miles to the east, where they would send over 100,000 residents of Amsterdam. But before they could send people, they had to find them. Invisibility, anonymity, was the key to survival.

But why would people pause, in the middle of a war, to have their pictures taken? One obvious answer is for identification papers (or false papers, more likely). Another is for keepsakes to be shared with friends and loved ones in uncertain times. Ironically, a Dutch resistance group earlier in 1943 had firebombed the Public Records Office in order to destroy data used by the Nazis to track down Jews. The Nazis had just opened a Vernichtungslager (death camp) at Auschwitz, 750 miles to the east, where they would send over 100,000 residents of Amsterdam. But before they could send people, they had to find them. Invisibility, anonymity, was the key to survival.

And there she is, on Roll No. 99, taken on September 20th, 1943: Alice Isaac, who resided at Jekerstraat 28. The street, south of the Amstel Canal, is lined with pre-war, four-story brick buildings. The Frank family lived at the end of the block (Alice and her sister attended the same school), but they had gone into hiding in 1942, when the occupiers sent Margo Frank a deportation notice.

A mark in the ledger indicates Alice Isaac never picked up the prints.

A mark in the ledger indicates Alice Isaac never picked up the prints.

And that squares with history. Sometime in 1943, 18-year-old Alice had received a message from her mother, who had been hospitalized. From the family apartment where she was living (alone and in hiding), she rode her bicycle to the clinic, only to find that it had been requisitioned by the Germans. She watched in horror as the patients were carried out on gurneys, loaded onto trucks, and sent to Auschwitz.

Before the month was out, Alice herself was picked up and shipped off to Bergen-Belsen. Belsen wasn't a Vernichtungslager but a camp where Jewish and Russian hostages were held in anticipation of eventual prisoner exchanges. The exchanges never occurred. Typhus swept through Belsen in the spring of 1945, killing tens of thousands of detainees, including the Frank sisters (who had been transferred from Auschwitz.)

Belsen was liberated by British forces in mid-April. In order to save as many victims as possible, the British immediately evacuated the infected compound and moved survivors to a "displaced persons" camp nearby. The Nazis had destroyed all personnel records, so it fell to refugee committees, to prisoners themselves, and to the Red Cross to identify both victims and survivors. Alice reported that she had a sister in Oregon, and that is where, in 1947, she eventually came. I was five, my brother was three, and Alice Isaac was our mother's sister, our aunt.

For Alice, then, a headlong rush of pleasant memories to drive out the nightmare. College (Lewis & Clark) in a serene setting in the suburbs of Portland. A handsome boyfriend, Ray Brown, just back from Navy service in the Pacific. Marriage. A long career as a teacher of art and languages in Oregon and California. When folks asked about her accent, inquired where she was from, she would reply, "Holland." And that was that.

And as she walled off her past from others, she cauterized it in herself. An attractive girl of twenty at the mercy of her captors: not something she wanted to relive in her mind.

My brother and I knew our aunt as an elegant, fastidious woman who would have her husband drive their Cadillac for weekly appointments at the beauty parlor and the nail salon. They had no children and kept to themselves, except for annual trips to Holland, France and Switzerland. But back home in Arizona, in retirement, they chose to live in a gated community because, she said, "Nobody here knows who I am."

Then, days ago, out of the blue, came this photograph, a glimpse into that earlier time. We had known her for decades as our mother's sister, we had watched her share a career and retirement with her doting husband, we had looked out for her after he passed away and her health declined. And now we know who she had been at the beginning of adulthood.

Last month, some 70 years after she sat for that portrait, Alice Isaac came to the end of her unexpectedly long and full life. Her childhood playmate Anne Frank did not survive Belsen, but the diary she kept in captivity became world famous and is regularly hailed as a triumph of the human spirit. Alice's legacy, to her family and to the thousands of students whose lives she touched, lies in those seven decades of post-war survival, no less triumphant in its anonymity.

Photo of Alice Isaac by Annemie Wolff, copyright Monica Kaltenschnee, courtesy of Stichting A. en H. Wolff.

PS: Most of the Wolff Foundation website is in Dutch, but there's a 3-minute English-language video, "Lost in History," on the homepage: http://stichtingwolff.nl

Leave a comment