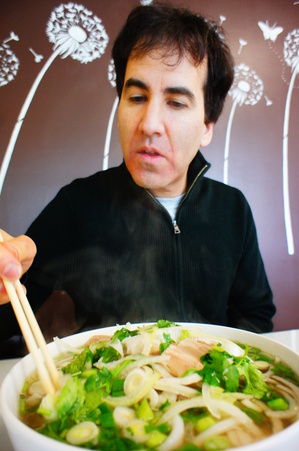

Jay Friedman goes where even the most jaded Caucasians rarely venture, down dark alleys and dusty strip malls, ducking into unmarked noodle parlors and dingy butcher shops. He's particularly keen on offal, and when the owner raises his eyebrows as if to say, "You no like," Friedman answers confidently, "Oh yes, I do like."

Jay Friedman goes where even the most jaded Caucasians rarely venture, down dark alleys and dusty strip malls, ducking into unmarked noodle parlors and dingy butcher shops. He's particularly keen on offal, and when the owner raises his eyebrows as if to say, "You no like," Friedman answers confidently, "Oh yes, I do like."

At Dong Thap, he dives into the bun bo hue, served with a cube of pork blood. At Hoang Lan, it's "a carnivore's delight of pork sausage loaf, pork blood cakes, beef tendon, and a huge ham hock." At Hokkaido, it's the pickled plum. At Huong Binh, the braised duck. He orders tripe and kidney at King Noodle, and devours freshly shaved noodles La Bu La. At Bar Bar, it's simply "the best pho in town." At Phnom Penh Noodle House, he revels in slow-cooked pork tripe and intestine; at Revel, he loves seaweed noodles with Dungeness crab. He travels to Edmonds for biang-biang noodles at Qin, and to Lynnwood for cold Korean noodles at Sam Oh Jung.

Korean, Chinese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai, Taiwanese, Filipino: the list goes on and on. The world of Asian noodles is complex almost beyond comprehension. Back in the old days, Chinese restaurants served "Chow Mein," and that was that. Eventually, diners learned that "mein" were noodles made from wheat, "fun" were made from rice. But even that was just the beginning. In Seattle's ethnically diverse Asian communities (Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Laotian), each has its own relationship with food, its own culinary traditions, its own sets of noodles. Udon and ramen, pansit and soba, banh canh and banh pho.

Fortunately, there's an expert on hand, an Eastcoaster who voted for Bernie Sanders when he was running for mayor of Burlington, a world traveler with a Japanese wife, a writer about the finer points of food (not just noodles), who also happens to have a full-time job as a sex educator.

Friedman, author of a sex guide called "The J-Spot," grew up on Long Island and took courses at the Cornell hotel school. He got a cooking job in Vermont, and ended up working for Planned Parenthood for seven years. He didn't like the "apologetic" approach to sex ed, so he went freelance on the college lecture circuit, but always, always, took the time to eat well.

He would frequently fly from the west coast to Asia. And one day in 2002, instead of passing straight through Narita he spent a couple of days in Tokyo, where he'd been set up by a PR firm with a personal tour guide, a young painter named Akiko Kino. By 2004 they were married and living in Seattle, where Friedman had settled in 1999. He wrote a book about his life on the road, the title taken from his lectures ("The J-Spot--A Sex Educator Tells All") and continues to travel the country speaking to college audiences and delivering "sex-positive" messages.

As it happens, one of Friedman's longtime colleagues in the sex-ed/sex advice business (one hesitates to call them competitors) is Dan Savage, who was for many years the editor of Seattle's alt weekly The Stranger, whose earliest Q&A advice columns were titled, simply, "Hey Faggot." Eventually, as society grew more tolerant of gay lifestyles, Savage became a sought-after media figure; in 2010 he launched the nationally recognized "It Gets Better" project to give hope to LGBT youth, and in 2011 he was named Seattle's "most influential person" by Seattle Magazine. This occured while Friedman also had a sex advice column, "Sexy Feast," in the competing Seattle Weekly. Both men were also on the college lecture circuit, Friedman full-time, Savage sporadically (and commanding much higher fees). "I think we are both advocate of sexual health and sexual freedom, and we are both passionate about sexual politics," Friedman says. Savage's primary forum is publication, while Friedman is better known as a performer and public speaker.

But Friedman also has a separate career as a food expert. In addition to his Sexy Feast column ("What Our Favorite Foods Teach Us About Sex "), he has a popular blog, Gastrolust. He co-authored the "Fearless Critic" guide to Seattle restaurants and is a regular contributor to the Serious Eats website,; he also curates the Seattle edition of a lively newsletter, "Eat Drink Lucky." Friedman documents virtually everything he eats with terrific photographs, too. What got him the most attention is a post he wrote two years ago on Gastrolust titled "What's Wrong with Ramen in Seattle?"

But Friedman also has a separate career as a food expert. In addition to his Sexy Feast column ("What Our Favorite Foods Teach Us About Sex "), he has a popular blog, Gastrolust. He co-authored the "Fearless Critic" guide to Seattle restaurants and is a regular contributor to the Serious Eats website,; he also curates the Seattle edition of a lively newsletter, "Eat Drink Lucky." Friedman documents virtually everything he eats with terrific photographs, too. What got him the most attention is a post he wrote two years ago on Gastrolust titled "What's Wrong with Ramen in Seattle?"

"Gomen na. That's Japanese for 'I'm sorry,' and something I want to state from the outset. I really hate to be a wet noodle about our ramen boom, but as someone who's spent considerable time in Japan, I've been feeling a little sad about the state of ramen in Seattle."

During one of his dozen trips, Friedman tuned into a TV show dedicated to ramen. In it, three experts traveled from restaurant to restaurant, judging ramen quality. A bad bowl? The expert would simply say Gomen na, and walk out.

Friedman savages the Seattle chefs who westernize the ramen. "You won't find ramen made with sous vide short ribs and candied carrots in the Land of the Rising Sun. But, all too often, that's the direction the dish is taking in the United States."

So he calls for a change in nomenclature. "If you're not trying to be authentic, then let's call your creation something new: Wramen. Pronounced double-u ramen, it indicates a version that you wouldn't expect to see in Japan."

He cites examples of wramen joints, some perfectly fine, like Brimmer & Heeltap (delicious, but spongy noodles), Tanakasan (strange soba-like buckwheat noodles). But Mighty Ramen (weak soup), Bloom (more weak soup), and Boom Noodle ("mushroom soup"). The real thing? Tsukushinbo (but only for lunch on Friday), 4649 Yoroshiku (again, lunch), Kuzuki (especially the yuzu-shio), Junya (tonkotsu), and Santouka (again, tonkotsu).

Friedman's ramen gold standard would be "Three Tens:" ten seats, ten minutes, ten bucks max. On the other hand, he most definitely doesn't recommend the same quick in & out when it comes to, ahem, more intimate relations.

Leave a comment