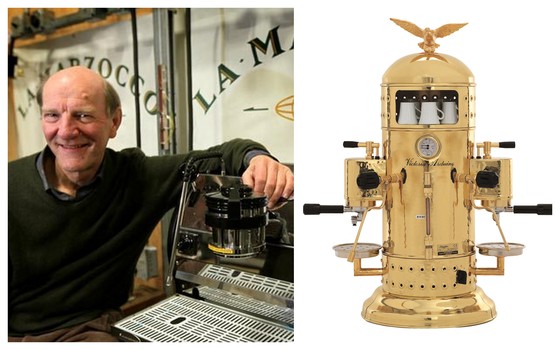

Kent Bakke, CEO of Marzocco USA, and the modern version of a Victoria Arduino espresso machine.

The marzocco is a heraldic lion, the medieval symbol of Florence. Not the fearsome bronze cinghiale (wild boar) that the tourists gawk at in the medieval city's central market, but a grey sandstone lion sculpted in 1420 by Donatello, no less, for the papal suite of the Medici palace. The "Marzocchesi" were the Florentines, in honor of their lion, even though there's no etymology connecting them. Mars, god of war, maybe.

Which brings us to la Marzocco, a brand of espresso machines, among Italy's finest. They're produced at a factory in the hills northeast of Florence, in a community called Scarperia that was long known for its knives. In 1927, production of espresso machines began there as well. Bear in mind: the north of Italy, with its abundant streams of running water to power mills, grinding wheels and presses, has always been a hotbed (as it were) of precision metal-working. There's also a 5-km race track, the Mugello Circuit, owned by Ferrari, on the outskirts of town; it's used as a test track and for auto and motorcycle races. Not far away are the Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, and Ducati factories.

Fast-forward to the 1970s in Seattle and a sandwich shop in Pioneer Square called Hibble & Hyde. The owner was a tinker named Kent Bakke, completely captivated by the winged, copper-clad Victoria Arduino coffee-making machine in the back. Needless to say, there was no internet; there were no instruction manuals, either. Bakke was on his own, but he managed to crank it up and make it work, and on a good day he would turned out half a dozen espressos. His business partner suggested a visit to Italy, so Bakke took himself to Scarperia and returned with a contract as La Marzocco's US importer. One of the first machines he sold went to a six-store chain just starting to serve espresso by the name of Starbucks.

Before long, thanks in large measure to Starbucks' buying La Marzocco machines for all its coffee shops, Bakke's company became La Marzocco's largest distributor outside of Italy, with offices in the UK, Australia, Korea, and so on. Then, 20 years ago, Starbucks needed 150 machines a month for its new stores. La Marzocco was less than thrilled by the challenge of meeting an order of this magnitude, so Bakke and a small group of investors bought 90 percent of the parent company. They promptly opened a second factory in Ballard to meet the demand from Starbucks.

For a long time, there was at least one La Marzocco machine in every Starbucks store, but in 2004 the Mermaid switched to push-button devices that required less skill on the part of the barista. Bakke closed the factory in Ballard and sold the distribution business to a Swiss company, even though, five years ago, he bought back the distribution rights. It was almost too late: in the interim, several former Bakke employees had opened competing businesses. Machines for home use, machines that allow baristas to control water flow and temperature. Still, says Bakke, "Our biggest competition is complacency."

Bakke's not the only player. Michael Myers has a thriving company called Michaelo Espresso that also sells and services several machines, including a brand called La San Marco. No relation to La Marzocco, though they're also made in the north of Italy.

Most of the big coffee wholesalers also have their own technicians, and plenty of one-man repair companies have set up shop as well.

But the news this season is that KEXP, the experimental radio station, is getting a new home at Seattle Center, and part of that space is a La Marzocco coffee shop and showroom. Bakke himself remains CEO of the company, the one that started decades ago with that one abandoned Victoria Arduino.

Leave a comment