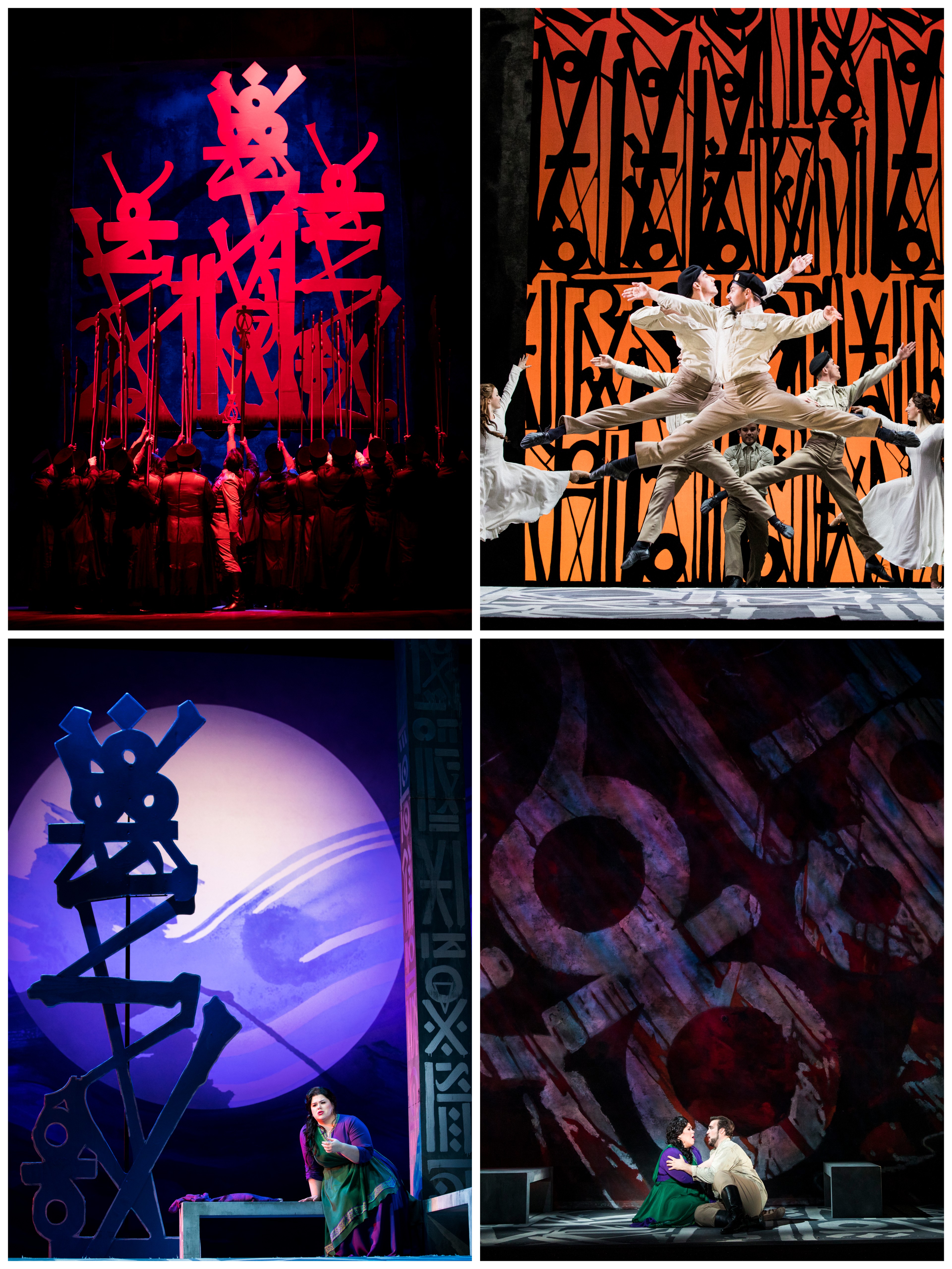

Leah Crocetto (Aida) and Brian Jagde (Radamès). Seattle Opera photos © Philip Newton.

It's one of the most extravagant of all operas. In fact, the sheer spectacle of Aida (that triumphal march! those elephants!) often outshines the music and singing. Not this time. Seattle Opera's current production of Verdi's masterpiece integrates the grand staging and the intimate personal love triangle. The first half is all show; after intermission, it's all about relationships.

In Verdi's time, Egypt was a metaphor for the newly unified Italian state, posing questions of private passion and political loyalty. The opera's characters can still be seen as stand-ins for contemporary politicians: the clueless warrior Radamès, the bitchy "entitled" princess Amneris, the idealistic slave girl Aida (whose father, unknown to her captors, is the "enemy" king). The questions, never fully answered: should personal loyalty (to friends, to family) outrank public duty (patriotism, service to country).

Grand opera finds artificial ways of framing these fundamental questions In Aida, the captured slave is in a relationship with the Egyptian military leader; in Romeo and Juliet, the lovers are from rival clans; in Norma, the high priestess even has children by her country's arch-enemy.

The director's job is to maintain the intimacy of the love triangle against the backdrop of pomp and circumstance, a task assigned for this production to Loren Meeker. But what about those elephants, you ask? In Portland, where the outdoor amphitheater adjoined the former zoo, they could bring in an actual elephant. Not at McCaw; not even a pony. Instead, this production uses an ornately decorated set (by Los Angeles street artist RETMA), dozens of choristers, a phalanx of supernumeraries and a troupe of dancers to portray the pageantry of the triumphal procession.

The opera's quiet moments (notably Aida's plaintive "O Patria Mia") are all the more intense for being framed by the grandiose set. In fact, a previous director of Aida called it "a chamber opera at heart." Well, that's like calling an F18 Hornet an overgrown Piper Cub; the first half of this Aida is a Blue Angels extravaganza through and through, even without the elephants. And then, as you know it will, everything gets worse and worse until Aida dies in her lover's arms at the final curtain.

Foortnote: Leading the orchestra was Seattle native John Fiore. His father George, who passed away five years ago, had served as the opera's chorus master for two decades, and young John grew up as part of Seattle opera's extended family, appearing as an onstage extra when needed and absorbing the company's culture. Fiore went on to a distinguished career as an opera director in Europe; he's currently the resident conductor at the Düsseldorf Symphony. While it's good to hear him back in Seattle, I would have preferred a less intrusive piccolo from the orchestra, and a bit of restraint from the three lead singers in their intimate moments. (Hard to do, understandably, when it's precisely that full-throated volume you want in the crowd scenes.)

I'll add a footnote of hesitation as well to the much-ballyhooed set design. Sure, you don't want to appropriate hackneyed pseudo-Egyptian hieroglyphics in this day and age (though why not, exactly?). What we get instead are vaguely Chinese abstract symbols that makes one wonder whether this is supposed to be Egypt, Moscow, Beijing, or maybe even Happy Hour at PF Chang. RETNA was scheduled to do a workshop for "local youth" but canceled and went back to LA before the premiere, so I couldn't find out.

And yes, audiences in Verdi's day expected a ballet, but, leaping lizards, as Orphan Annie would say, so many leapers! So much leaping!

Leave a comment